Have you ever thought about how we navigate and perceive the world around us?

In How People Learn — The Brain Basics, I have described the basic principles of brain functioning. But as powerful as it is, our brain is a black box that relies on various sensory systems to get information from the outside world for processing.

Without input from those sensory channels, we are just a conscious sack of bones, muscles, and organs that wouldn’t know about the existence of anything around us.

But how many senses do we have? To answer that, we have to differentiate between the two main types of stimuli first: external (outside our bodies) and internal (generated by our organism itself). For this article, let’s focus on the external stimuli since that is the only way to get information about our environment. Therefore, those are:

- Vision

- Hearing

- Touch

- Taste

- Smell

There is a sixth external sense (sense of balance, responsible for perceiving gravity and acceleration), but this article will focus on those five only, since the sense of balance represents one’s position in the world, without offering much information about the surroundings.

Interestingly, all those senses are pretty localized, except for one. We can only see with our eyes, hear with our ears, smell with our nose, and taste with our mouth. However, we can experience touches (and a range of other sensations like pressure, vibration, temperature) with our skin (and hence, entire body).

Touch was the first sense organisms had to develop to navigate the unfriendly world around them. Like taste, touch aids in analyzing objects in direct contact with the body. Conversely, vision, hearing, and smell have evolved to interpret the world at a distance.

Collectively, all external sensory systems allow humans to navigate and interact with the world around them:

- we perceive light (a short range of the electromagnetic spectrum) with our eyes;

- we perceive sound with our ears;

- we perceive chemical substances with our nose and mouth;

- we perceive temperature, position, and motion with our skin;

Senses Throughput

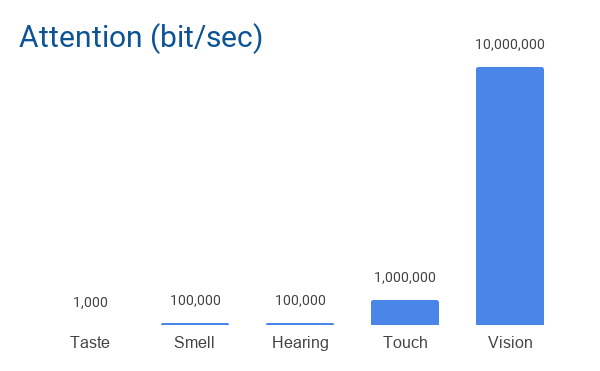

All these sensory channels have a capacity for how much information they can carry. Surprisingly, the difference between the throughputs of various channels is striking. In his book, “Presentation Secrets,” Alexei Kapterev defines the throughput capacities as follows:

Therefore, we have the following throughput capacities:

- visually we perceive around 10,000,000 bit/sec;

- through touch we can perceive around 1,000,000 bit/sec;

- hearing and smell has 100,000 bit/sec throughput;

- taste has only 1,000 bit/sec throughput;

That is some tremendous difference between various senses. I will not focus on the “bits/sec” unit of measurement since it is not that relevant for now. What is relevant is the capacity relative to each other. We get a massive amount of information through our eyes, a tenth of that through our skin, a hundredth of that through our ears and nose, and a tenth of thousands of that through our mouth.

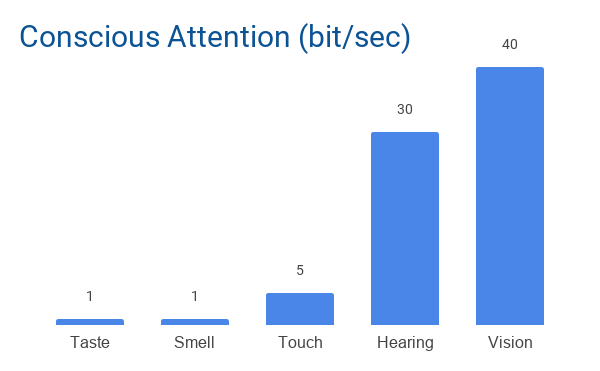

You might wonder why touch is on the second place and not hearing. It turns out that the chart above represents the unconsccious attention throughput amounts—that is, information we perceive without deliberately paying attention to it. What about the conscious attention throughput amounts? Kapterev covers that as well:

The conscious senses throughput is incredibly small in comparison with the unconscious ones:

- vision has still the highest capacity of 40 bit/sec;

- hearing took over touch with 30 bit/sec on the second place;

- touch has 5 bit/sec throughput;

- smell and taste both have only 1 bit/sec;

Kapterev’s work is based on Danish scientist Tor Nørretranders, who in 1991 defined the Bandwidth of Senses in his book “The user illusion: Cutting consciousness down to size.” Although there is still no precise measurement of conscious throughput (29 years have passed since Nørretranders' attempted to measure it), more recent findings (2013), display a similar trend regarding the conscious capacity. For instance, Richard Epworth defines conscious throughput depending on the task at hand (operating on and memorizing different things), and it can vary between 2–18 bit/sec:1

Source: humanbottleneck.com

Therefore, if we consciously perceive so little, what happens with all that information we sense unconsciously? That is a fascinating question that scientists are trying to understand fully. Some of that information is still processed unconsciously by different regions of the brain for threats and extraction of relevant features. I will cover more of it in one of the next posts on attention.

Brain’s Virtual Reality

Since we consciously are able to perceive so little information, we have to interpret a lot of things and greatly rely on our previous experiences when interacting with the world around us. As much as we would like to experience reality as objective as possible, we are living inside our heads much more than we think.

What we experience as The World is nothing but a recreated representation of the actual world in our minds based on what we know about it already. You might be sitting or lying on the couch when you read this, and it would be effortless for you to go to the kitchen with your eyes closed. You would probably even not have to slow down, because you have a model of your house/flat in your mind already. Another example is your commute to work: if you have your car, you know the path, and you just drive to your work, listening to your favorite songs, and singing along. Or, if you have to use public transport, you are probably reading or listening to something while on your way to the workplace.

But things change drastically when you don’t have any prior experience of something. Imagine you are driving in a new big city and you need to find your Airbnb flat in the city center. Because your conscious throughput is small, you have to “shut down” any irrelevant sensory channels: you do not eat while driving, turn off the music, and might not be talkative. All your attention is directed on the road, semaphores, signs, and other cars. Even then, you might occasionally take the wrong turn because you were distracted or had to take more time to process information and decide.

If to consider the walking example—imagine you are in a new city and want to get to a place you’ve long wanted to visit. Not only will you plan your path in advance, but you will have to stop and analyze things at each pace: subway stations, bus stations, number of blocks you’ve walked, etc.

Therefore, as powerful as it is, a marvel of biological engineering, the brain compresses and prunes information incredibly well before it reaches our conscious attention. So, to compensate for the small amount of conscious processing, the mind keeps an internal representation of your environment at all times, allowing you to put those tens of bits per second of conscious attention to good use at the cost of relying on that reconstructed (and eventually outdated) representation of the world.

If you liked this article, consider subscribing below and following me on twitter (@iuliangulea).

Bottleneck - Our human interface with reality: The disturbing and exciting implications of its true nature by Richard Epworth, 2013 ↩︎