Have you ever thought about how people learn? What happens inside your brain when you learn some new information or practice a novel skill? And is there a way to enhance the outcomes of learning?

This article is the first in the series on “How People Learn,” in which I invite you to embark on a journey toward a better understanding of the most sophisticated construct in the Universe—the human brain.

And I would like to start with and exercise. You will need a piece of paper and something to write with. When you have them ready, write down the following sentence:

I can write fast and beautiful.

It should be pretty easy, if not effortless, isn’t it?

Now, I would like you to write the same sentence one more time, below the first one, but at this time, use the opposite hand (let’s call it the inexperienced hand). Therefore, if you initially wrote the sentence with your right hand, switch your pen to the left side and vice-versa.

Think about how was it now? Unless you are a person that learned to write with both hands, I bet your second sentence is not that beautiful, and you wrote it not that fast either. When I was lecturing at the university and doing this exercise with my students, it took them somewhere between 3 to 10 times longer to write down the second sentence than the first one.

If you did follow through and write the two sentences, I highly encourage you to write it with the inexperienced hand for the third (and last) time below the first two sentences. It should be slightly easier to write it now, but there will still be inadvertent trembling and awkward lines.

How do you explain this? You know how each letter should look, how it should be tilted, and how curved it should be—you possess the theory at 100%. Yet very few can draw a well-rounded letter ‘a’ or ‘o’ with their inexperienced hand. It is very likely that you are also holding your pen as though it weighs 5kg, and your hand is trembling in the process.

A Primer On Brain Structure

The answer resides in the structure of the brain. As you might know, the brain consists of brain cells called “neurons.” Let’s represent a neuron as in the next image.

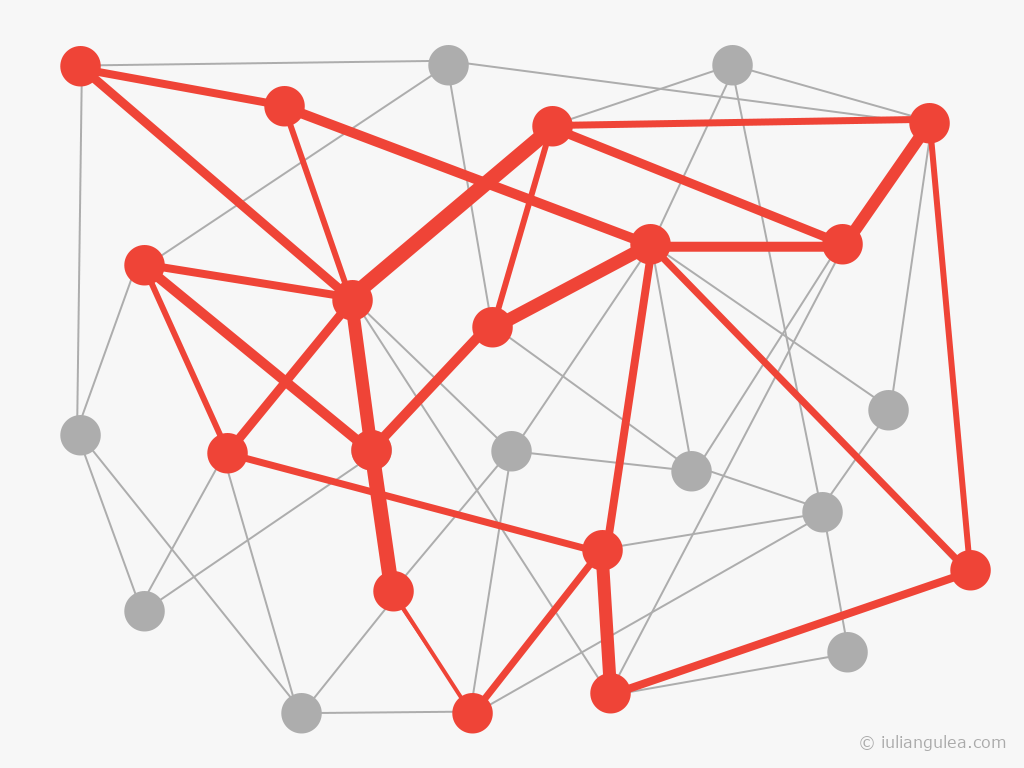

Neurons connect to other neurons, forming a complex net of interconnected brain cells. According to the latest plausible estimates,1 there are 86 billion neurons in a human brain. And each cell can connect to up to ten thousand other neurons. That is an astounding amount!

I will not attempt to draw such a complex, interconnected set of neurons as in a human brain. I will not try to represent even the 302 neurons with its ~7,500 connections of a roundworm.2 Instead, I will rely on this extremely simplified version of a brain group of interconnected neurons to describe some essential events that take place inside one’s brain.

All our memories, experiences, skills, thoughts, sensations, etc. are encoded and stored within those interconnected brain cells.

Neural Patterns

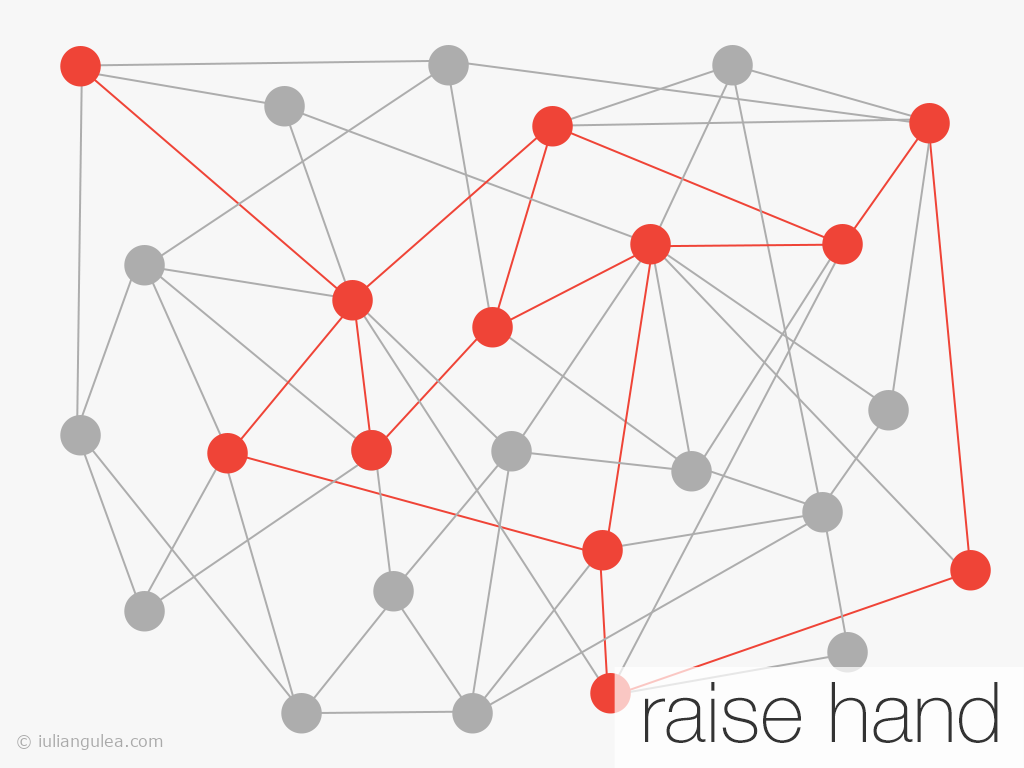

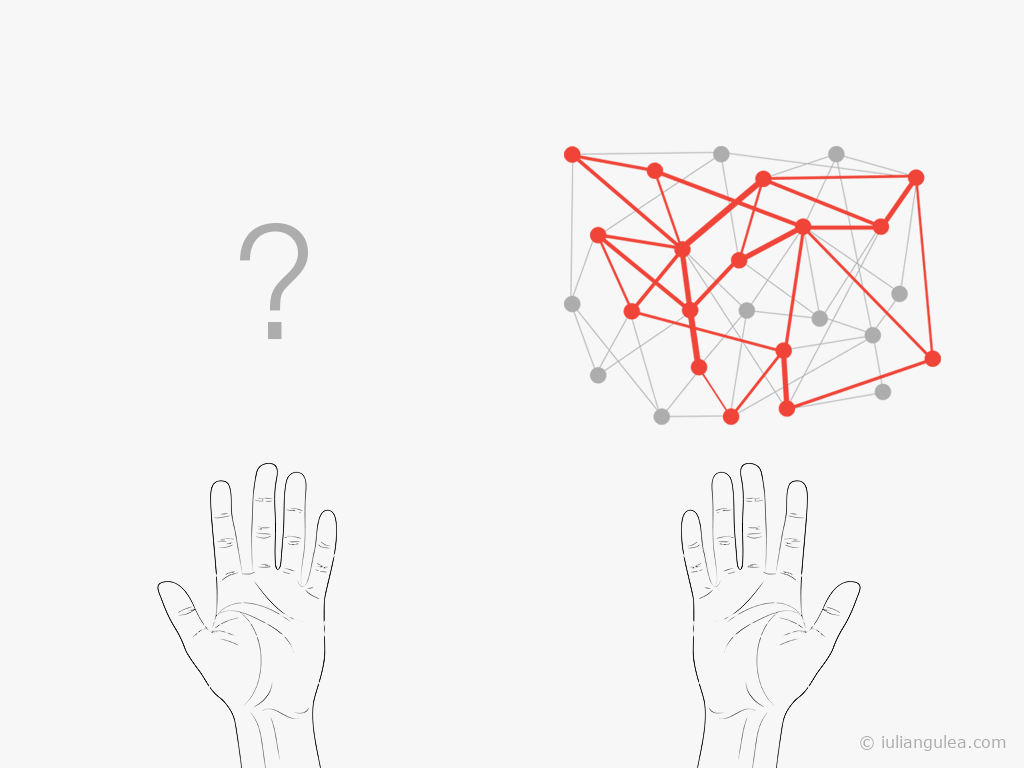

Neurons communicate with each other through electric pulses and chemical neurotransmitters. Whenever we do something or think about something, specific neurons responsible for that action or thought get activated by sending impulses to each other. For instance, when you raise your right hand, a particular group of neurons gets activated simultaneously:

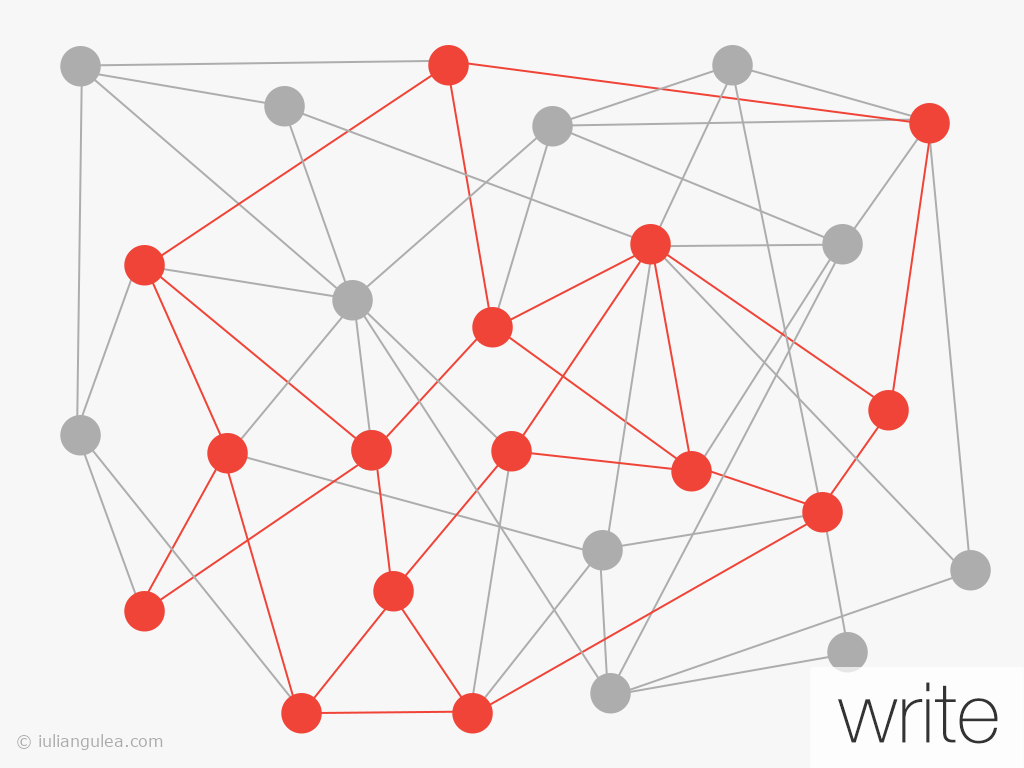

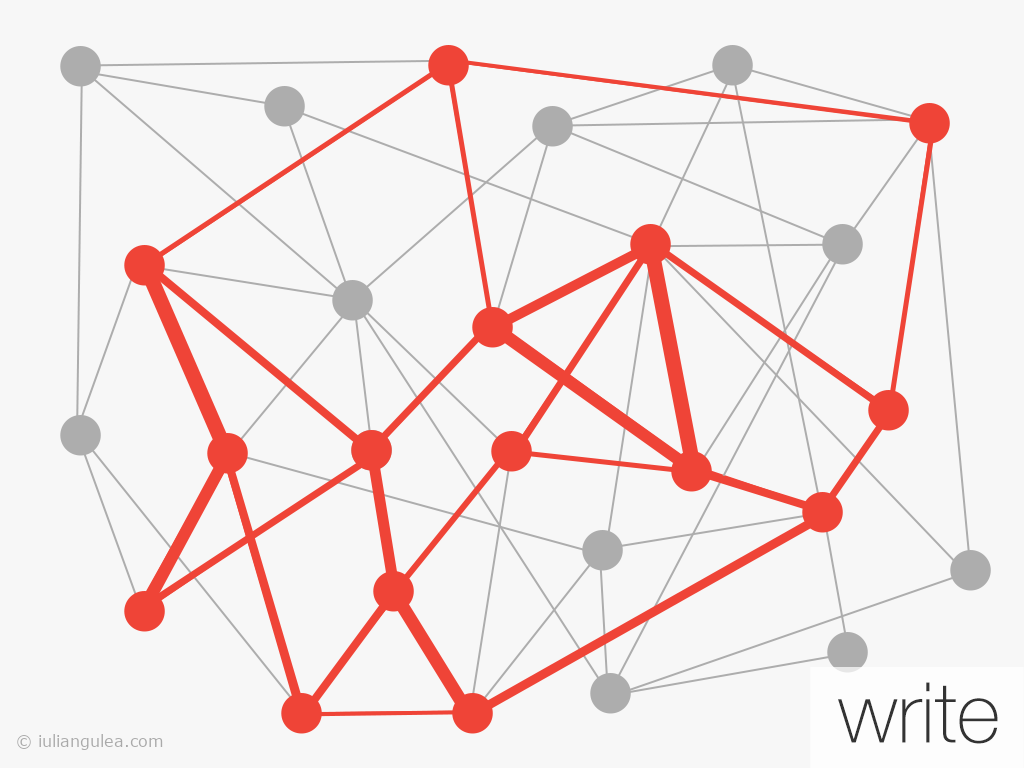

When you write, another group of neurons fires together:

These groups of neurons that fire together are called neural patterns. When activated, they are responsible for specific actions or thoughts. Keep in mind that the examples above are extremely simplified. Real patterns spread throughout large portions of the brain and can incorporate billions of neurons.

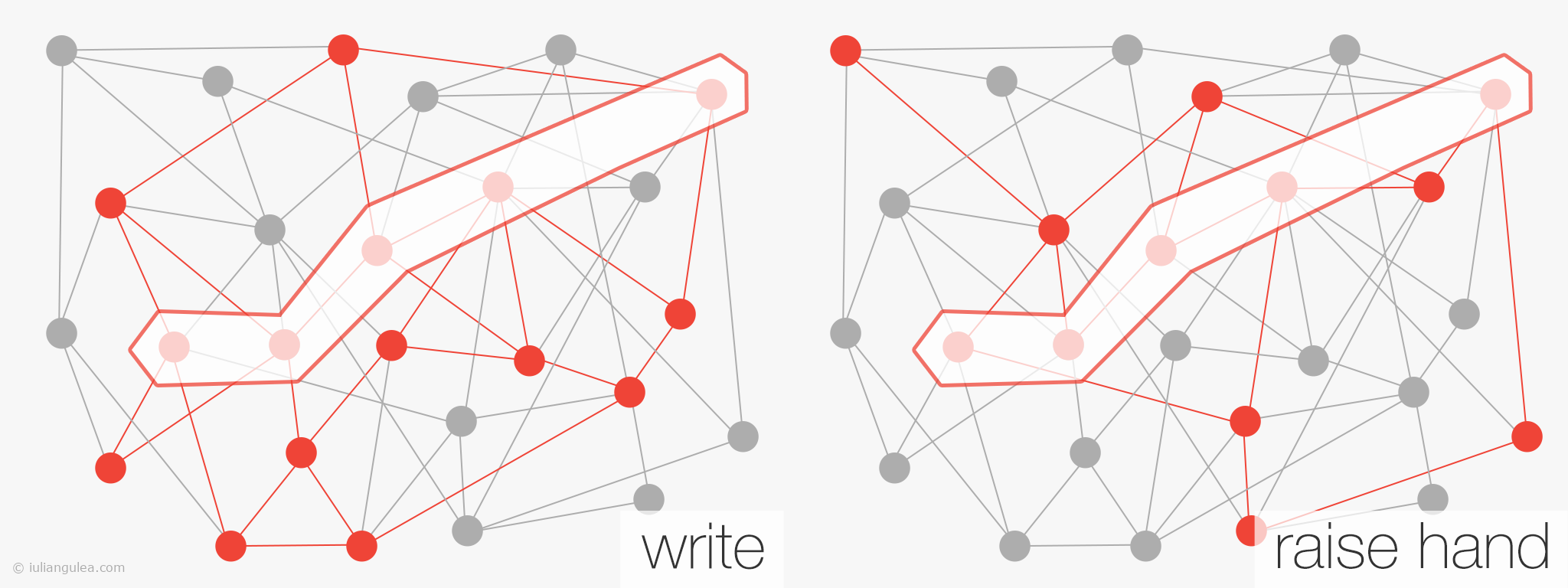

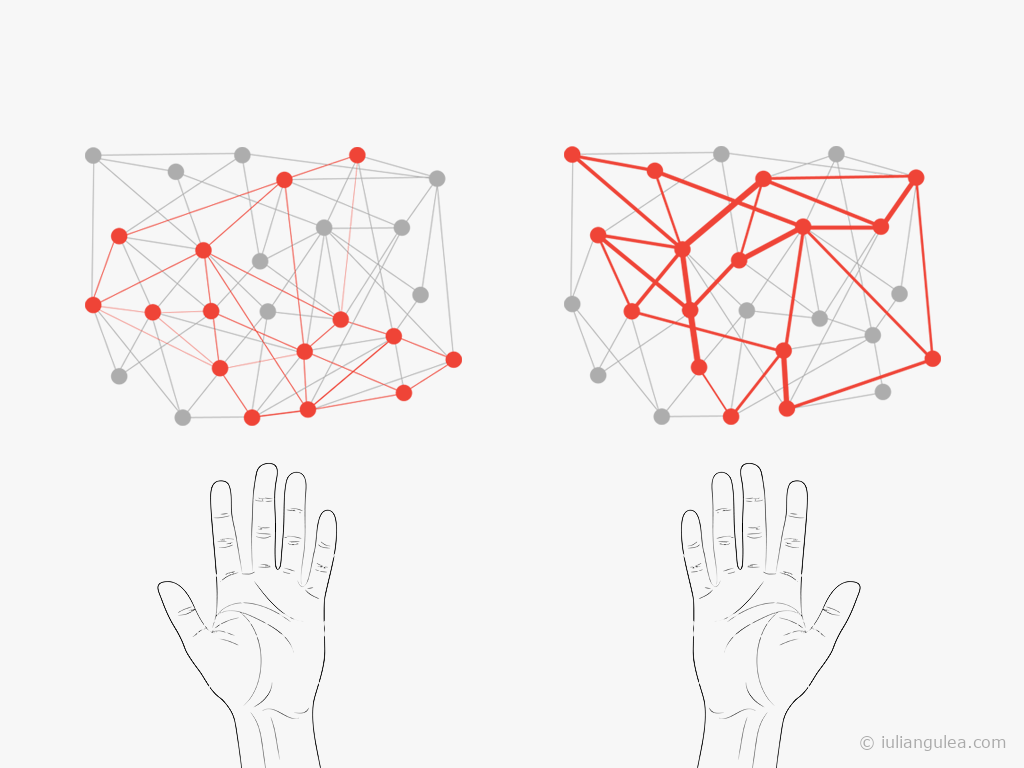

Note that these patterns can overlap, meaning that the same neuron or even huge chunks of neurons can be part of several patterns. Below you can see that “writing” and “raising hand” share some of their neurons.

This explains the associative nature of memory and our experiences—as you are thinking about something specific (i.e., your favorite childhood cartoon), parts of the neural patterns that get activated are also parts of circuits related to other memories. That gives you the possibility to “hop” from one memory to the other. Just try to recall an instance of when you watched that cartoon and let your mind wander for some time. You’ll be pleasantly surprised with where it might lead you.

It Is Not Only About The Number Of Connections

Besides the number of neurons, one essential thing that characterizes a pattern is the strength of its connections. A connection can be strong or can be weak, and it represents the relationship between two neurons.

In the image above, the thicker lines represent more durable links. The stronger a bond is, the easier it is to communicate between neurons through it, and the harder and longer it takes to break it apart. We’ll see the implications of this in the next section below.

Therefore, activities that we know how to do and with which we have experience and thoughts that we think about often have strong links between neurons in their associated patterns. Conversely, skills we have just begun to practice, or thoughts we rarely think about have weak circuits.

To make an analogy, think of a link between two neurons as a pathway during winter.

Source: Needpix.com

Initially, when you have to go from point A to B, there is no path, so you have to walk through deep snow, leaving a narrow trail in the process. Have you ever walked in deep snow? That is exhausting, and so forming new circuits is. But the more you travel along that path, the more trodden it becomes, and the easier it is to walk it. Eventually, it will become a wide sidewalk that you can use to travel between point A and B effortlessly. But if you will abandon that path, the snow will gradually claim it back, until one day it will just disappear.

The Process Of Forming New Circuits

Thus, all the information we know and skills we possess are encoded in our brains' neural patterns. It is time to discuss the process of brain circuits administration. Research from the last 100 years has incredibly advanced the understanding of how the brain rewires itself. This process is called Neuroplasticity.

Neuroplasticity, also known as brain plasticity, is the ability of the brain to undergo biological changes ranging from the cellular level (i.e., individual neurons) all the way to large-scale changes involving cortical remapping.3

One of the fundamental principles of how neuroplasticity functions is the idea that individual connections within the brain are continually being created, strengthened, or removed, largely dependent upon how they are used.4 Thus, neurons that are in close proximity and fire at the same time tend to form new connections (or, if they are already connected, the link strengthens). But in case a relationship is not used, it weakens over time, and eventually, it disappears, leaving the two neurons disconnected.

This theory was first introduced by Donald Hebb in 1949, and it is often summarized as “neurons that fire together, wire together."

Going Back To Writing

Knowing all that about our brain circuits and how they function, let’s analyze the previous writing exercise and describe it using our freshly acquired information.

When you first wrote the sentence with your “regular” hand, you have used your existing, robust neural pattern responsible for writing with that hand. That’s why it felt natural and seamless.

But when you switched to the other hand, no pattern was found responsible for writing with that hand, so a new one started to emerge.

Different neurons fired together while you were striving to write each letter, and new links started to form. In case you followed my advice and wrote the sentence for the third time, the writing process should have flown more easygoing. That’s because the new pattern is strengthening in the brain! The more you will practice writing with that hand, the easier it will become for you.

This simple exercise demonstrated a fundamental truth that we sometimes ignore:

Knowledge != Skills

We have a sound pattern responsible for the knowledge about each individual letter and another circuit that is responsible for writing those letters. If you would take one thing out of this article, please remember this: knowledge does not necessarily mean skills. You might know something (the alphabet), but this does not imply than you will be able to write those letters.

This principle applies to many areas of our lives. For instance, reading a book on self-improvement, sales, public speaking, or anything else, does not magically teach you the skills described in those books. Reading those books will strengthen your neuronal pattern related to knowing. It’s like learning the shape of letters, the theory. Only when you begin to write, when you apply the theory into practice, then you start developing the patterns responsible for the actual skills.

There is much more to possessing an ability than just knowing the theory:

- Knowing the shape of the letters is not enough to be able to write. You need to develop proper muscle movement to hold the pen and draw the lines that form the letters.

- Knowing some five steps to efficient sales is not enough to be a salesman. You need to learn to listen to customers, understand what relevant questions to ask, process the information you receive, formulate correct benefits that solve their problems, etc.

- Knowing how to write code does is not enough to be a programmer. You need to understand how to define the architecture of a project based on the requirements, how to organize and structure your code, how to test it, etc.

It does not mean that the theory is not essential. Conversely, knowledge about a domain helps you gain experience faster since you can interpret how good or bad the outcome of your practice is. As described in The Pyramid Of Mastery, knowledge and skills are complementary. You cannot master a domain by excelling at only one side of the pyramid. It is when you know both the building blocks of a domain with their corresponding rules, and you practice enough to operate with them and gain experience, then you are on your path toward mastery. Then your brain rewires itself to create integrated, robust neural patterns that not only encode knowledge about the shape of the letters, but which allow you to write any text flawlessly.

The Foundation Of Learning

Now you know the general principle of how the brain functions. The implications of these principles are vast and can help you understand lots of other things about your behavior, habits, the optimal environment for learning, and many more. For instance, in How People Learn — Human Senses, I describe how people perceive information and what are the capacities of each sensory channel. Stay tuned for more articles on this topic and make sure to subscribe below to receive new articles directly into your inbox and also follow me on twitter (@iuliangulea).

Equal Numbers of Neuronal and Nonneuronal Cells Make the Human Brain an Isometrically Scaled-Up Primate Brain — Frederico A C Azevedo, Ludmila R B Carvalho, Lea T Grinberg, José Marcelo Farfel, Renata E L Ferretti, Renata E P Leite, Wilson Jacob Filho, Roberto Lent, Suzana Herculano-Houzel. ↩︎

The roundworm is the only organism to have its whole connectome (neuronal “wiring diagram”) completed. List of animals by number of neurons — Wikipedia. ↩︎

Neuroplasticity — Wikipedia. ↩︎

What is Neuroplasticity? — ScienceBeta.com. ↩︎