We all have big goals in our lives. Some have to write their thesis; others work on a big project; others prepare to run a marathon.

Be it related to health, economics, technology, or any other domain, and regardless of the scale of impact (a personal goal or one that impacts a group of people or a company), accomplishing one big thing implies completing several tasks. And those tasks can be further split into smaller assignments.

I wrote about it previously as part of increasing one’s productivity. It is practical to divide the entire workload into chunks that can be managed and performed easier. This process of breaking down tasks has a limit, though. After several iterations, you’ll get to an atomic task—one that cannot be divided anymore.

A Breakdown Example

Let’s consider a specific and very relevant use-case given the current situation we live in: exercising.

Suppose your goal is doing a 30-minute workout on any given day. That workout can be broken down into six different exercises (first breakdown iteration). Let’s say one of those exercises is doing squats, and you would like to do two sets of 20 squats each (second and third breakdown).

Now, you cannot go further as the most atomic task is a squat. It doesn’t make sense to separate the movements to lower your body from those that straighten you up.

From “Planning” To “Doing” Is A Longer Path Than It Seems

One might think that a 30-minute workout might be too long. Take some time to ponder on how much effort would it take you to do such an activity? And we constantly find excuses on why we cannot do it (although, in most cases, we are just lazy).

Therefore, let’s reduce it to a single set of 20 squats. Take a moment to think how much effort would 20 squats take you now? Much less, but is it enough to motivate you to do those 20 reps?

I find it interesting that it is not only the number of squats that prevents me from doing them but also the change in activity from what I’m currently doing.

Change 20 to 15 or even to 10 or 5, and it will still be hard to do them regularly. So what’s the issue here?

The Cost Of Switching Activities

What if we’d bring that number down to one squat? It’s close to nothing, but you might still not do it.

Therefore, it is the first squat that is the hardest. Right now, if you’d stop reading this and did one squat, you would not have a problem doing one more afterward, and then one more, and then 5, 10, even 20.

Once you are in the process, it is easy to continue. The second squat takes almost no effort at all. You have the momentum, and you just follow along. And to build momentum, you have to put in the effort. You have to stop from what you are doing (while having momentum in whatever activity you’re in at that moment), shift your focus, prepare, and start doing the other activity. But it is not the only thing that prevents you from doing something.

The Cost Of The Upcoming Activity

Before starting something, we subconsciously estimate the effort needed to perform the job and only proceed if we are able to accomplish it. Otherwise, what is the point of starting something if you cannot finalize it?

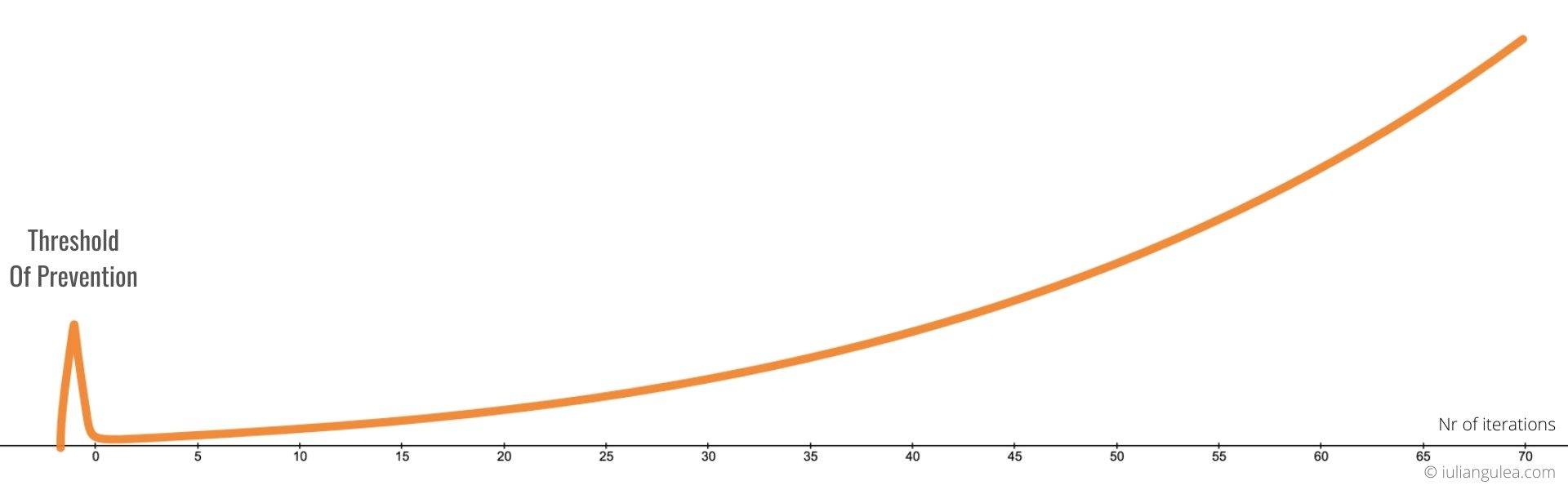

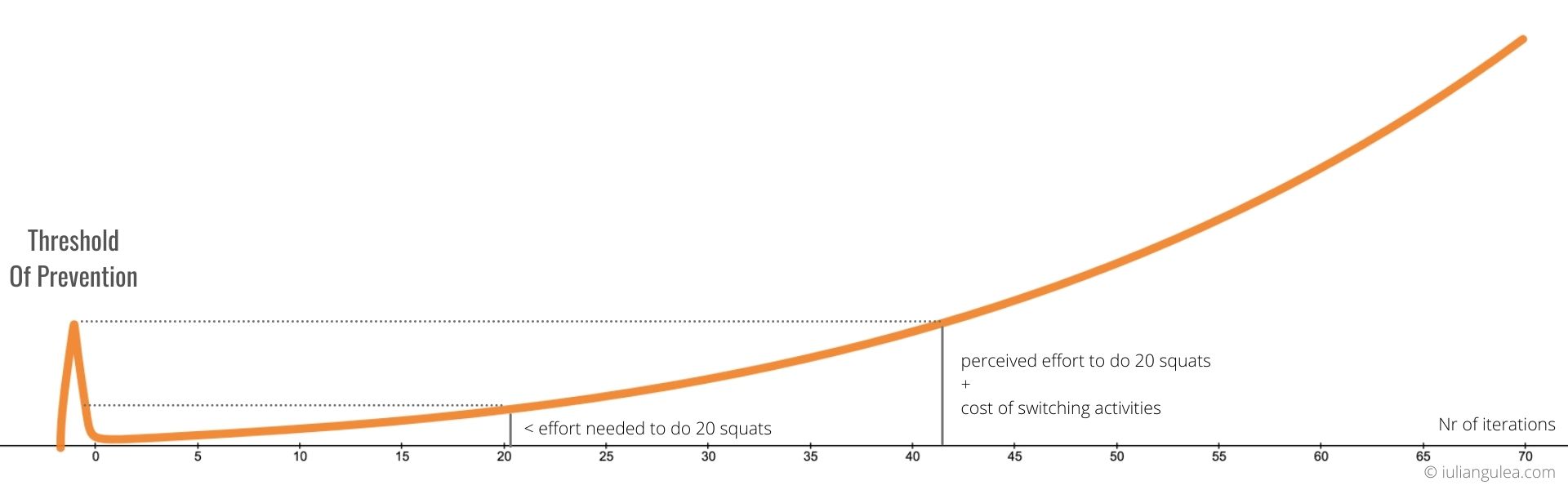

Put these two things together, and you get the following approximation of the effort needed for an activity that consists of many iterations:

That spike in the beginning is why people often quit before even starting something. I call it the Threshold of Prevention. It’s like a wall that prevents you from doing things you would like to do but for which you don’t have enough motivation.

The perception of the necessary effort consists of the combined effort needed to switch activities and finalize the planned job. Besides the cost of switching activities, you have to “pay the entire price” of a task beforehand. Our minds estimate whether we will be able to achieve our goal of 20 squats and add it to the equation.

Thus, we have the initial threshold that is higher than the energy needed for 20 squats because it contains the cost of switching tasks, but also because we are terrible at estimating things. You need to do 20 squats, but you are prepared to do around 40 of them.

The good news is that you can use this subjective perception in your favor. Instead of planning to do 20, plan on doing a single squat. Thus, you lower the perceived necessary effort to do the entire thing (that consists of one squat), leaving you only with the costs of switching activities. Then, if you feel like doing more — just do it. And the chances are high that you will do more since you have already made the heavy lifting by doing that first one.

An Experiment

Let’s do a simple experiment that will surprise you if you follow along.

If you didn’t do it previously, think of what it takes you to make 20 squats?

Now think about what does it take you to make a squat? One simple squat. Can you do it now? Come on, follow along—just a single squat. You’ll feel better about yourself.

And while you’re at it, just in case you’re not against doing one more, stick to it.

From Exercising To Everything Else

Making squats is only an example. This principle applies to many other actions.

Do you want to write an article or a book? Start by writing a single sentence or a paragraph in one sitting rather than an entire chapter, then, once you’re at it, keep writing until you feel like doing so.

Do you want to clean your room? Start by doing a minor cleanup (workspace, chair, or any other small sub-zone). If you feel like doing more — continue with the rest of the room.

Do you want to build a project? Start by writing it down on a piece of paper and put together a list of things you need for it.

Do you want to read a book? Start by reading 1 page or even two paragraphs, then, once you’re at it, keep reading if you like it.

The Threshold of Prevention consists of both the effort needed to switch activities and the estimated total energy of the task you are about to do. By decreasing the number of planned repetitions, you lower the perception of the required effort for the job, making it easier to start the activity.

It does not absolutely guarantee you will follow along. However, any atomic action you perform will still bring you closer to your desired goal, even if you will stop after it.

Conclusion

To sum up:

- The difference between 5 to 10 to 20 squats or 10 to 50 to 100 written words is minor. It takes little additional effort to keep doing something you already do.

- The first iteration incurs an additional effort due to the switch of activities and the upcoming task’s size. This threshold is a subjective one, but it frequently prevents you from doing those things you would like to. Once you are past that threshold, it is much easier to keep doing the activity of your choice.

- To lower the starting threshold, trick your brain into planning to do a single repetition/atomic task. Once you are past the Threshold of Prevention, adjust your plan to do as many reps as you need. It will be much easier to do now.